Deficiencies at F699: Emerging Trends in the Enforcement of New Regulations

Timothy Legg

2/13/2024

Revisions to the state operations manual, appendix PP (guidance to surveyors), were promulgated in 2016 and ultimately scheduled for implementation in 2017 and 2019. However, the pandemic delayed the implementation of these revisions. The revisions were implemented in three phases, with the most recent revision to phase 3 implementations occurring in February 2023.1 One of the major changes in the revised regulations included tags for which many skilled nursing facilities were not adequately prepared to address, specifically F699, which addresses the provision of “trauma-informed care.”

Revisions to the state operations manual, appendix PP (guidance to surveyors), were promulgated in 2016 and ultimately scheduled for implementation in 2017 and 2019. However, the pandemic delayed the implementation of these revisions. The revisions were implemented in three phases, with the most recent revision to phase 3 implementations occurring in February 2023.1 One of the major changes in the revised regulations included tags for which many skilled nursing facilities were not adequately prepared to address, specifically F699, which addresses the provision of “trauma-informed care.”

While some advocacy groups have pointed out that skilled nursing facilities have had six years to prepare for the implementation of these regulations, the reality is that meeting these new regulatory requirements has been far from easy. The revised regulations require skill sets not ordinarily found among skilled nursing facility employees for various reasons. Procuring the necessary specialty services to address the requirements of these regulations is particularly problematic not only because America is amid a mental health provider shortage2, 3 but also because mental health issues among nursing home residents are increasing, placing an even greater burden on an already stressed mental health system. Behavioral health disorders are estimated to impact between 65 to 90 percent of nursing home residents.4

In this first article of a two-part series, we will review the requirements at F699, what is known about the emerging patterns of deficiencies being cited under this regulation, and, most importantly, consider strategies skilled nursing facilities can use to achieve compliance with the requirements of F699. In the exploration and presentation of publicly available CMS data for preparing these articles, deficiencies were “generalized” without providing specific details (as outlined in the facility’s CMS-2567), as this could inadvertently lead to the identification of the facilities that received deficiencies. While this information is certainly available in the public domain, the intention of these articles is educational—to learn about deficiency patterns at F699 and not single out any facility. Readers wanting more specific details about these citations can download Full Texts of 2567 Statements of Deficiencies directly from the CMS website.

Trauma-Informed Care and the Difficulty in Providing It

The regulation at §483.25(m) F699 requires that the facility “ensure that residents who are trauma survivors receive culturally competent, trauma-informed care in accordance with professional standards of practice and accounting for residents’ experiences and preferences in order to eliminate or mitigate triggers that may cause re-traumatization of the resident.”5

While the text of the regulation appears straightforward, it fails to account for the many intricacies involved in the competent provision of trauma-informed care. For instance, how to assess trauma, how to develop trauma-informed treatment plans, treating trauma which depends on the availability of mental health providers within the facility to provide care and services to residents with a history of trauma. Although requirements at F850 demand qualified social workers in a facility that has 120 beds or more6 (although state laws may be more stringent), there are no requirements for social workers in facilities with fewer than 120 residents. Additionally, coursework in undergraduate social work programs may not adequately address the intricacies of psychological trauma and its treatment. Similarly, nursing education programs require only brief experiences in dealing with individuals with diagnosed mental illness, typically through clinical rotations at inpatient psychiatric units, and as such, do not adequately address psychological trauma. The absence of these educational experiences results in facilities that are challenged regarding “who” can adequately address resident needs.

In addition to the paucity of staff in the nursing facility skilled in providing trauma-informed care, nurse aide training program curricula typically do not address trauma. A recent survey that I undertook of several nurse aide textbooks failed to reveal any content related to trauma-informed care. While it is tempting to say that this content requires the intervention of the staff development professional, nursing home professionals employed in staff development are typically registered nurses (who, again, have not received training in trauma-informed care). The inadequacy of behavior health (BH) education and psychiatric training of nursing home staff is “associated with subpart provision of BH services in this care setting.”7

Facilities are limited in terms of their knowledge, skills, and abilities to provide trauma-informed care despite regulations requiring it. Exploration of evolving trends in deficiencies received at F699 through available CMS survey data shows that the number of deficiencies at F699 has increased from 11 in 2022 to 145 in 2023.

States Most Frequency Cited and What Deficient Practices Were Found

From 2022 to 2023, Pennsylvania facilities received the most deficiencies at F699 (33 different facilities in the state received deficiency citations), followed by Michigan (14 different facilities in the state received deficiency citations), Massachusetts (12 different facilities in the state received deficiency citations), and Minnesota (11 different facilities in the state received deficiency citations). The scope and severity of deficiencies at F699 across all states ranged from levels “D” through “L,” with most deficiencies in 2023 at the “D” level.

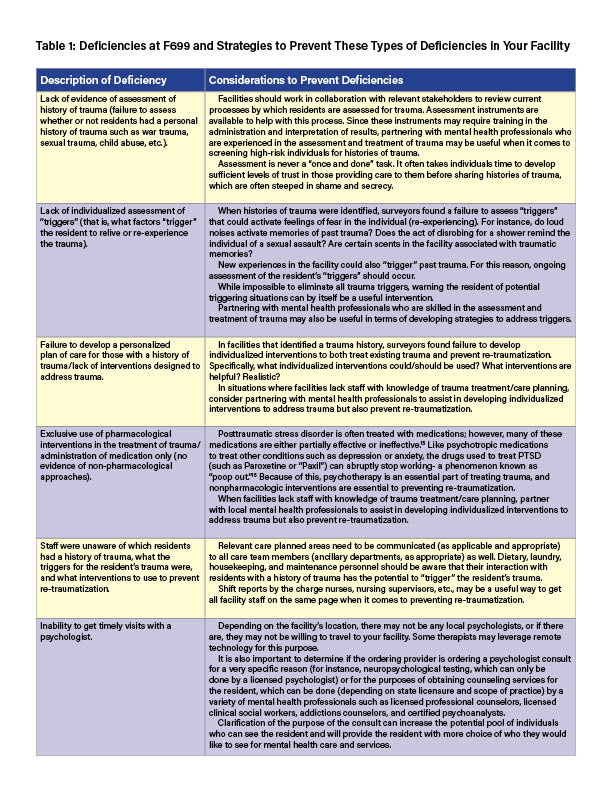

Examination of the circumstances that led to deficiencies at F699 is useful as it will provide your team with information that they can use to assess practices at your facility.  Table 1 represents an amalgamation of the issues that were identified on the CMS 2567 for each facility that received deficiencies at F699. They are reported as broad themes, along with suggestions for preventing deficiencies.

Table 1 represents an amalgamation of the issues that were identified on the CMS 2567 for each facility that received deficiencies at F699. They are reported as broad themes, along with suggestions for preventing deficiencies.

Mental Health Provider Shortage and F699

Nearly half of all Americans will have a mental health (including substance use) disorder in their lifetime.8 Behavioral health disorders impact between 65–90 percent of nursing home (NH) residents.9 Approximately 45 percent of Americans (approximately 150 million people) live in a mental health shortage area.10 These figures do not take into consideration the fact that the population of older adults with Alzheimer’s disease is projected to rise to 13.8 million by 2060 from the current estimated rate of 6.7 million.11 Data specific to the number of nursing homes in mental health shortage areas is not available; however, facilities that I have provided consultation to in Pennsylvania and New York have reported multiple challenges with finding mental health providers.

The number of professionals willing to provide care in nursing homes is problematic. Psychiatrists, for instance, are the “least likely” medical specialty willing to accept Medicare because of inadequate reimbursement.12 Between 2011 and 2019, the number of psychiatric/mental health nurse practitioners willing to treat Medicare patients increased by 160 percent.13 Unfortunately, their use in many nursing homes is limited by restrictive state laws governing the independent practice of nurse practitioners and CMS restrictions on “non-physician practitioners.” Specific to the psychotherapy services that can mitigate mental health issues, until 2023, only licensed psychologists, clinical nurse specialists, and licensed social workers were able to provide services to Medicare recipients.

However, effective January 1, 2024, both licensed professional counselors (LPCs) and licensed marriage and family therapists (LMFTs) will be covered by Medicare Part B to receive reimbursement for providing care to Medicare recipients.14 This new infusion of therapists eligible for reimbursement for services can potentially increase the number of mental health professionals available to help both residents and facilities and may be able to help prevent deficiencies at F699.

However, effective January 1, 2024, both licensed professional counselors (LPCs) and licensed marriage and family therapists (LMFTs) will be covered by Medicare Part B to receive reimbursement for providing care to Medicare recipients.14 This new infusion of therapists eligible for reimbursement for services can potentially increase the number of mental health professionals available to help both residents and facilities and may be able to help prevent deficiencies at F699.

Timothy Legg is a board-certified gerontological and psychiatric/mental health nurse practitioner, licensed psychologist, licensed professional counselor, and state-licensed/nationally certified nursing home administrator. In addition to his private practice, he provides direct care and services to older adults in nursing homes as well as consultative services to nursing homes in Pennsylvania. He is an approved directed in-service provider by the Pennsylvania Department of Health.

References1. United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2023). Revisions to State Operations Manual (SOM), Appendix PP. https://www.hhs.gov/guidance/sites/default/files/hhs-guidance-documents/R211SOMA.pdf 2. The Commonwealth Fund. (2023). Understanding the U.S. Behavioral Health Workforce Shortage. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/explainer/2023/may/understanding-us-behavioral-health-workforce-shortage3. Tampi, R. R. (2023). Geriatric psychiatry in the US. Psychiatric Times, 40(12), 20.4. Orth, J., Li, Y., Simning, A., Temkin-Greener, H. (2019). Providing behavioral health services in nursing homes is difficult: Findings from a national survey. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 67(8), 1713-1717. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16017. 5. United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2023). Revisions to State Operations Manual (SOM), Appendix PP. https://www.hhs.gov/guidance/sites/default/files/hhs-guidance-documents/R211SOMA.pdf 6. United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2023). Revisions to State Operations Manual (SOM), Appendix PP. https://www.hhs.gov/guidance/sites/default/files/hhs-guidance-documents/R211SOMA.pdf 7. Orth, J., Li, Y., Simning, A., Temkin-Greener, H. (2019). Providing behavioral health services in nursing homes is difficult: Findings from a national survey. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 67(8), 1713-1717. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16017. 8. The Commonwealth Fund. (2023). Understanding the U.S. Behavioral Health Workforce Shortage. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/explainer/2023/may/understanding-us-behavioral-health-workforce-shortage9. Orth, J., Li, Y., Simning, A., Temkin-Greener, H. (2019). Providing behavioral health services in nursing homes is difficult: Findings from a national survey. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 67(8), 1713-1717. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16017. 10. Kaiser Permanente, Institute for Health Policy. (2023). Addressing the Mental Health Workforce Shortage. https://www.kpihp.org/blog/addressing-the-mental-health-workforce-shortage/ 11. Tampi, R. R. (2023). Geriatric psychiatry in the US. Psychiatric Times, 40(12), 20.12. Bishop, T. F., Press, M. J., Keyhani, S., & Pincus, H. A. (2014). Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(2), 176-181.13. Gerlach, L. B. & Maust, D. T. (2023). Falling off a cliff: Psychiatric care of nursing home residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 71(4), 1014-1016.14. Department of Health and Human Services. (2023). 2 CFR Parts 405, 410, 411, 414, 415, 418, 422, 423, 424, 425, 455, 489, 491, 495, 498, and 600 CMS-1784-F RIN 0938-AV07 Medicare and Medicaid Programs; CY 2024 Payment Policies under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Changes to Part B Payment and Coverage Policies; Medicare Shared Savings Program Requirements; Medicare Advantage; Medicare and Medicaid Provider and Supplier Enrollment Policies; and Basic Health Program. Retrieved from https://public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2023-24184.pdf 15. Stahl, S. (2021a). Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology (5th ed). Cambridge. 16. Stahl, S. (2021b). Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology prescriber’s guide (7th ed.). Cambridge.

More Information: