Researchers Puzzle Over Mealtime Dementia Care

Bill Myers

2/20/2014

Playing music, moving to “family style” service, and other meal reforms appears to help people living with dementia, but experts say they don’t know how to find the best course (or why it works).

British researchers say they’ve surveyed thousands of studies on different approaches to making those with dementia more comfortable while they eat, but, like Churchill’s notorious pudding, the research lacks a theme.

“Most of the studies were small, and the reporting was of poor quality,” University of Exeter researcher Rebecca Whear writes for her colleagues in the March issue of the Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. “We identified only 11 studies involving 265 individuals that met the inclusion criteria for this review.”

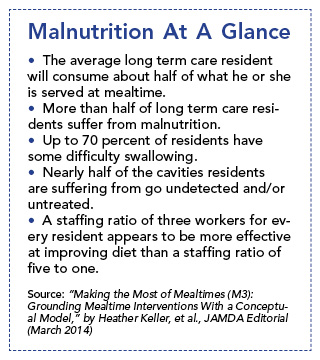

More than half of long term care residents suffer from malnutrition, which cascades into other problems, from infections to falls, experts say. Keeping residents with dementia calm during meals is, therefore, critical for providers and the residents.

The studies show, generally, that rethinking meal service has “some positive influence” in cutting down on the stress for those with dementia, Whear says. “The evidence in our review suggests that simple and inexpensive interventions can help to alleviate agitated behaviors,” she says.

The problem, Whear and others say, is that it’s hard to test outcomes because the profession hasn’t yet agreed to terms. “Well-designed … controlled trials are need to test the generalizability of these results and to build evidence for best practice in this area,” Whear says. “Effective, simple, nonpharmacological interventions have the potential to improve the residential care environment at little cost, while reducing negative dementia-related behaviors and improving the mealtime environment.”

Whear is not the only one who hopes for more careful attention to mealtime interventions.

In the same issue of the journal, Whear’s findings get a hardy “Amen” from University of Waterloo Professor Heather Keller and her colleagues. “We would add to this recommendation that intervention research needs to be based on a conceptual framework grounded in current evidence that demonstrates that there are several influences on the varied activities (e.g., arriving, eating, waiting, socializing) that occur during a mealtime, and there are several intermediate … and ultimate outcomes” to consider, Keller writes.

Keller and her colleagues say that family-style dining or even the Eden Alternative-designed “household” models appear to improve both the nutrition and the morale of those with dementia. The problem is, residents and caregivers all over could really benefit if someone could figure out how, and why, those

approaches work, the Waterloo researchers say.

“Use of person-centered strategies, such as accommodating individualized needs and preferences during mealtimes, has been qualitatively explored, but has yet to be quantitatively assessed with respect to improved outcomes,” Keller says.

In order to think differently (and clearly) about mealtimes, providers ought to borrow the approach of restaurant and food retailers, Keller and her colleagues say. Keller leans on “The Five Aspects of Meal Model,” a complex-adaptive formula that considers everything in the room (table, lighting, décor), in the kind of meeting taking place (family meal, social club), the food itself, and how the place is managed.

Those four elements are added up in what restaurateurs calling “the dining atmosphere,” Keller and her colleagues say.

“This framework suggests that there is an intersection of food or meal quality and mealtime experience,” Keller writes. “We contend that these two domains (meal quality and mealtime experience) are key to food intake [behavior problems] and other mealtime outcomes, and that a third domain of ‘food access,’ which can limit or alter food intake, also should be considered when designing interventions.”

Overall, Keller and her colleagues say, providers (and researchers) should think as broadly as possible when considering how to make meals more effective and less stressful for residents.

Meals “are complex,” Keller writes. Providers should weigh carefully all the variables that go into a meal, from a resident’s ability to feed herself to staff training, to the dining room décor, to government funds for, or regulations of, food. That more holistic approach to the problem will surely yield better results than the single-minded focus of previous efforts, Keller says.