In the morning stand-up meeting, the charge nurse reports that Mrs. Jones (pseudonym) was upset that she was not offered cake when most of the other residents had been given some. Mrs. Jones has diabetes, her blood sugar is not well controlled, and her physician has ordered a diabetic diet. The staff offer her alternatives, but they note she is getting more upset and has started to decline going to meals and activities. She has told her nurse assistant that “it’s not worth living this way.”

It is the quintessential challenge for health care providers in long term care: balancing the rights of each resident to make decisions and the multiple risks that may co-exist in supporting those choices. Balancing these sometimes conflicting responsibilities often feels like walking a tightrope without a net, but just as with performers, it gets better with practice.

Resident Rights and Duty of Care

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website contains a document for residents titled, “Your Rights and Protections as a Nursing Home Resident,” and within the first paragraph it talks about residents’ rights to be informed and to make their own decisions. The bottom line is that people do not give away their civil rights on taking up residence in a long term care community.

All health care professionals have the duty of care, to avoid behaviors that could reasonably and foreseeably cause harm. So, on this surface is where the conflict occurs, between the resident right to self-determination and the professional and organizational responsibility to minimize potential for harm.

Informed Decision

Several important caveats to consider are capacity and risk. Does the resident have the capacity to understand the risks and make an informed choice? The key factor here is that capacity is a legal term and not something that is determined solely by the staff. Only when an advanced directive or power of attorney has been triggered would the staff look to another individual for decision making.

The second important issue is that the resident has been made aware of the risks and benefits of different options. Additionally, the options cannot be putting other residents at risk.

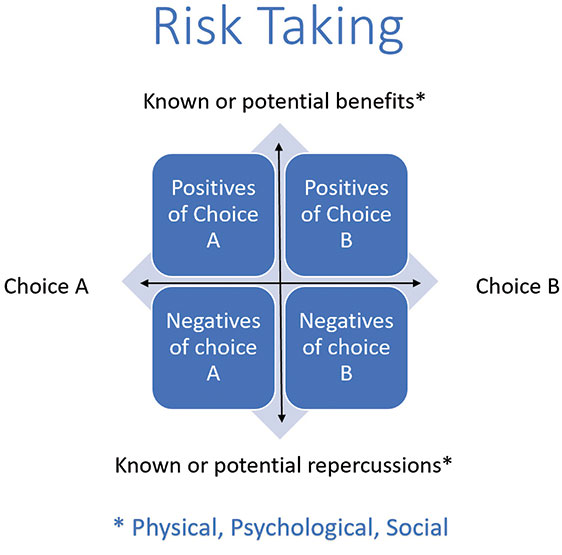

Defining Risk

Geriatrician G. Allen Power, MD, has described risk as “the chance that something occurs that is different than is expected.” Health care professionals tend to focus on the negative risk, concentrating on the bad things that could happen. However, there are positive risks as well, that something better than expected may happen.

It is also important to keep in mind that risks are not only physical, but they can also be psychological and social. Health care professionals have been taught to focus primarily on the physical risk. This is what gave rise to the era of “physical restraints” since they were thought to increase physical safety (they were wrong), and there was little to no attention to the psychological and social implications of their use.

In their own lives, health care professionals take physical risks every day; they eat, walk, take a shower. Yet rarely do they think of these things as risky because they do not expect to choke, trip on the stairs, or slip in the shower. People value doing those activities, so the tradeoff of a small potential negative event is outweighed by the positive effect gained in doing it. No one has led a risk-free life.

Like everyone else, older adults must balance freedom of choice against safety/risk: It is the balance between what is important to them and what is important for them.

Health care has historically been paternalistic by making decisions for people, presuming to be acting “in their best interest” of safety over autonomy, deciding what is important for the resident or the organization providing the care. What health care has often failed to recognize is that there is dignity in risk; making choices is integral to experiencing life.

With advancing resident rights, health care practitioners are realizing that learning what is important to the resident, and having open communication to make informed decisions, can support a solution that is both important to the resident and more likely to be the best for them as an individual. It means being flexible in addressing individual resident challenges and recognizing that one-size-fits-all rules and regulations are what depersonalize care delivery. Just like risk is not the same to each person, the response of an organization and staff must have nuance as well.

Thus, the challenge arises not when the resident makes a choice, it is when he or she makes a choice that the health care professionals or the community do not agree with. This is not to say the health care professional should not make recommendations based on training and expertise, but the resident’s values and life experiences must be elicited and understood first, since all decisions must be viewed through their lens.

Risk should be reviewed for potential physical, psychological, and social impact. Beyond these it must address both the potential benefits and negative implications of taking one action versus another, including taking no action at all.

A realistic view of both the likelihood and potential severity of any consequences needs to be mutually established and understood to the best of the team’s ability. Additionally, decisions should be evaluated through a lens of proportionality; that is, are the suggested interventions or even the need for interventions at a level commensurate with the issue at hand? Like the physical restraint example listed earlier, restricting all mobility because some mobility is unsafe was not a proportional response.

Documenting Risk Discussions

Like most areas of long term care, documenting the decision-making process and resident involvement is critical. A written record of the assessment of options, potential positive and negative implications, and recommendations from professionals involved is required to show informed decision making.

Clear documenting should reflect that the resident is aware of the potential positive and negative outcomes as could reasonably be known to the group. Keep in mind, this could be a negotiation where each side may need to readjust their options to find a decision that can support the resident and be accommodated by the home. Managed risk contracts may be an option to show this process as an addendum to a care plan.

Ongoing Review and Learning

The plan of care should be reviewed on a regular basis to see if the decision still meets the resident’s needs, values, and preferences. These ongoing reviews will also help the resident to see if their decisions are having the desired outcome or if additional interventions may be needed to support or alter their decision.

Staff should also use reflection on the process, the decisions, and a review of what is working and not working as they adapt to a more person-centered approach. It may be uncomfortable to accept when their professional judgment was considered but the resident chose a different direction. However, seeing the person, their values and preferences, and how those contributed to the resident making a different choice can reframe the care delivery process, so the resident is truly at the center of the health care team.

It is also important for everyone to recognize that these decisions are not written in stone, just on the care plan. They can and should be edited as more information is revealed via resident and staff experience.

A trial “failure” should be a learning experience, where in this situation with these variables something did not have the outcome expected. Proper implementation, documentation, and ongoing review and support to minimize potential risk within the resident’s life choices are the keys to balancing risk and autonomy while providing person-centered care.

For Mrs. Jones, a restrictive diet is more likely to help her physically by keeping her blood sugar more tightly regulated, but her lack of engagement and socialization with meals and activities is impacting her psychologically and socially. Further dialogue is clearly needed to determine reasonable options for monitoring food selection and the risks to her health, while staff need to better understand her life and health care priorities.

Based on this real-life example, it was mutually agreed that Mrs. Jones’ care plan was updated to keep the diabetic diet for meals, but have it relaxed for a “regular” snack in activities with her friends. With this she completed a larger portion of her meals, and there was not a significant change in her blood sugar regulation with the new plan.

Based on this real-life example, it was mutually agreed that Mrs. Jones’ care plan was updated to keep the diabetic diet for meals, but have it relaxed for a “regular” snack in activities with her friends. With this she completed a larger portion of her meals, and there was not a significant change in her blood sugar regulation with the new plan.

Cathy Haines Ciolek, PT, DPT, FAPTA, is president of Living Well With Dementia®, providing education and consulting to improve well-being and create positive expectations for aging adults. She can be reached at cciolek@livingwellwithdementiallc.com or 302-753-9725.