The (Over) Reliance on the CMS Five-Star Quality Rating System

Steven Littlehale

6/18/2024

In March, I had the privilege of presenting a session titled “Rethinking Five-Star: From Consumer Rating System to Industry Driver” to an engaged audience comprising primarily external stakeholders. These stakeholders, while not directly involved in the day-to-day operations of nursing homes, hold a significant interest in the outcomes and trends within our health care segment.

Reflecting on the session several weeks later, I am struck by the pervasive influence and widespread acceptance of the Five-Star rating system in our industry. Five-Star began in 2008 as a well-intentioned initiative by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to help consumers make choices. Today, it is one of the most potent influencers of nursing home profitability. Hospital discharge planners, lenders, real estate investment trusts, attorneys, politicians, and the media all use Five-Star to make decisions, direct patients, and reward or penalize nursing homes.

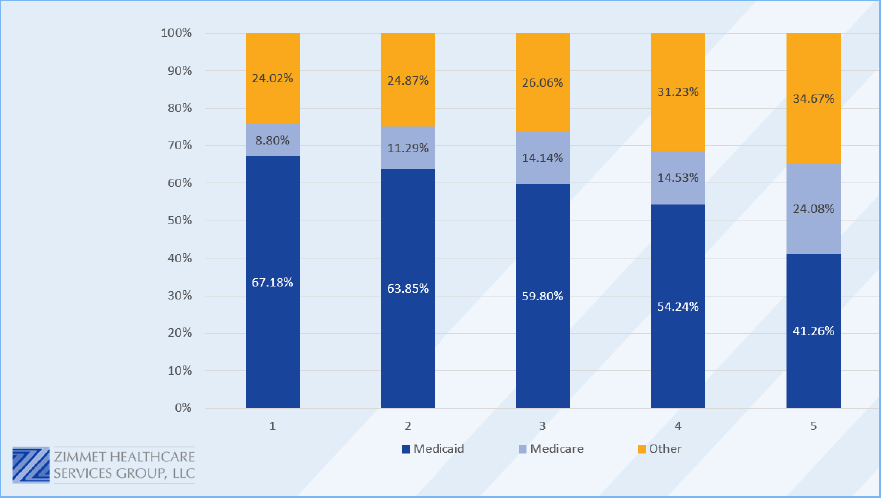

In preparation for the session, our analytics team conducted a comprehensive study delving into the relationship between Five-Star ratings and financial performance. We utilized metrics such as occupancy rates, Medicare and private-pay ratios, and Medicaid proportions as indicators of profitability. Our analysis segmented the industry following the most recently available Five-Star Overall ratings, from one to five stars.

This segmentation was quite telling, given the industry's reliance on Five-Star performance for critical decisions regarding patient referrals, financing, and other investments. Nursing homes with higher Five-Star ratings have different occupancy experiences and payor mixes. Chart 1 demonstrates the differences.

Chart 1

CMS policies motivated the achievement of a three-star rating to access desirable benefits, partnerships with accountable care organizations (ACOs), and other CMS Innovation initiatives, and the private sector has eagerly followed suit. Some markets (Medicare Managed Care and other alternatives) make four-star status a prerequisite for membership in preferred networks. Consequently, nursing homes maintaining a three-star rating or above are more likely to secure partnerships and networks conducive to profitability, while those falling below face challenges with lower occupancy and revenue but higher Medicaid populations.

Holly Harmon, RN, MBA, LNHA, FACHCA, senior vice president of quality, regulatory, and clinical services, American Health Care Association (AHCA), was not surprised by these findings and went further. “It has been understood for years that higher quality leads to overall improved performance, not only financially, but also in areas such as customer experience measures,” she said.

What motivates CMS to tie Five-Star ratings to Affordable Care Act (ACA) initiatives? Despite diligent scrutiny, we have yet to establish a clear correlation between Five-Star ratings and the triple aim of the ACA. In our initial exploration, we examined rehospitalization rates and observed that discrepancies between lower- and higher-rated facilities diminish when adjusted for case mix. This suggests that financial stakeholders (in this example ACOs) who rely on Five-Star ratings for network decisions are receiving a minimal return on their investment.

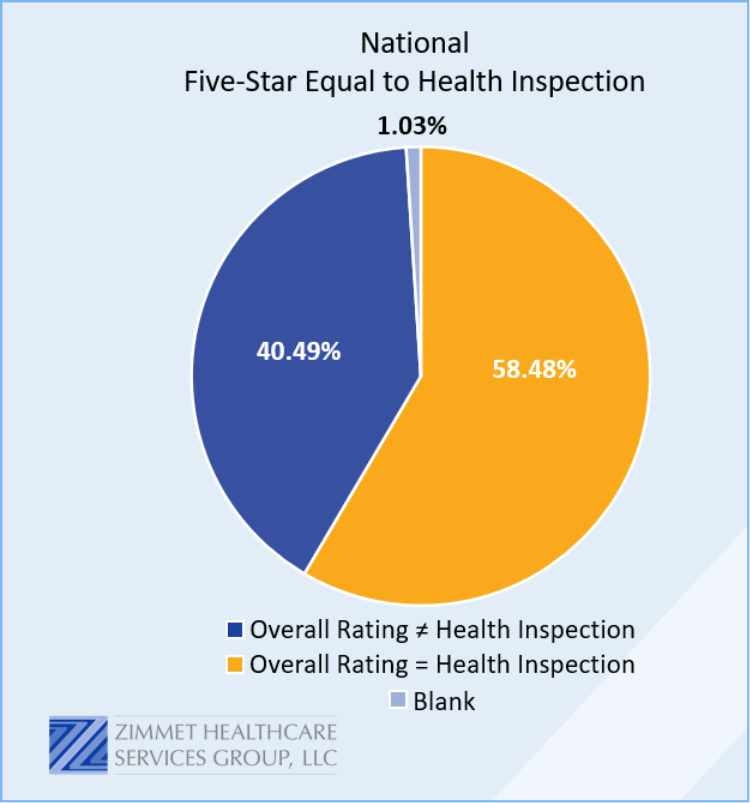

Survey and certification performance is the driver of the Five-Star Overall rating. Across the nation, 60 percent of nursing homes’ overall rating is equal to their Health Inspection rating (see Chart 2). Where survey results are best understood in the context of their local survey office, they have consistently proven to be far from an objective measurement of quality. Add to that the significant delay in survey, and most nursing homes’ current Five-Star rating cannot be seen as representative of the care they are delivering.

Chart 2

Jay Gormley, chief investment officer and chief operating officer at Zimmet Healthcare Services Group, shared this about Five-Star: “A few years ago, a large segment of the lending community was using Five-Star Overall rating as a proxy for overall quality and in some cases as a mortgage contingency. For some providers, if ratings dropped below a certain threshold, the loans would be in technical default.”

Gormley continued, “Due to the recent changes in Five-Star and the apparent lack of longitudinal validity, utilization and perception of the Five-Star metric has changed for many lenders. Lenders are now focused on the specific quality and performance data that underlies the Five-Star ratings rather than the Five-Star overall score. This change reflects a growing realization that Five-Star is a much more subjective measure than originally perceived.”

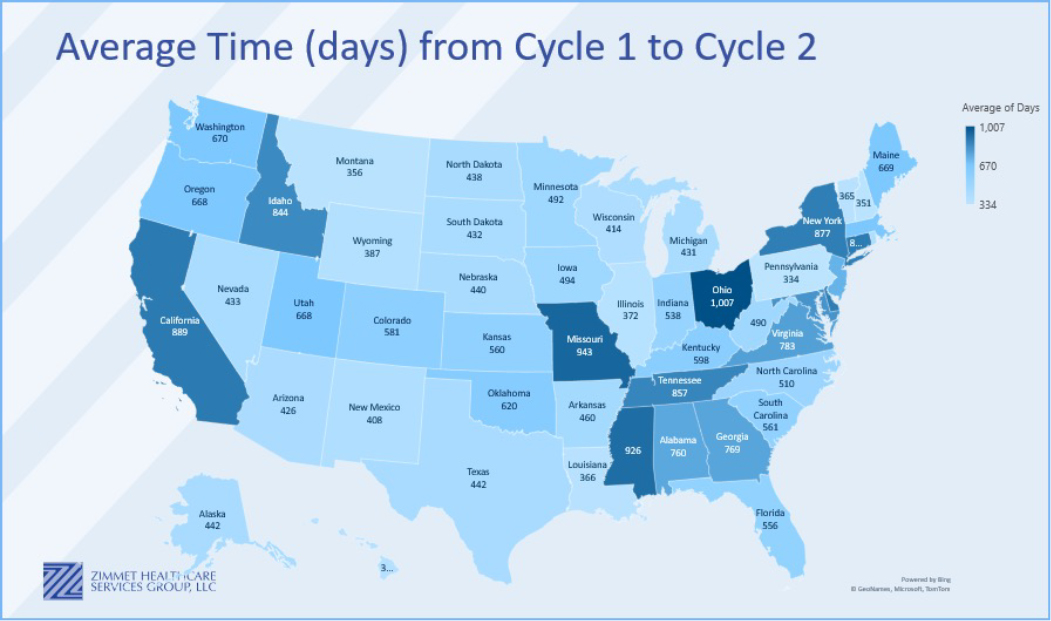

It's evident that stakeholders—broadly defined—must seek alternative metrics for decisions on patient placement, financial investment, lending/refinancing, and network inclusion. The “predictive power” of Five-Star ratings for profitability is waning, prompting a shift toward more robust evaluation frameworks. As well, some CMS initiatives, such as Risk-Based Surveys, show great promise for shortening the length of days between Cycle 1 and Cycle 2 assessments (see Chart 3 for how those lengths vary between states).

Chart 3

While Five-Star ratings have served as a valuable benchmark in the past, their relevance in predicting profitability and driving industry decisions is diminishing. As stakeholders navigate evolving health care landscapes, it's imperative to embrace a multifaceted approach that transcends simplistic rating systems.

While Five-Star ratings have served as a valuable benchmark in the past, their relevance in predicting profitability and driving industry decisions is diminishing. As stakeholders navigate evolving health care landscapes, it's imperative to embrace a multifaceted approach that transcends simplistic rating systems.

Steven Littlehale is chief innovation officer at Zimmet Healthcare. He is a gerontological clinical specialist with more than 30 years of experience ranging from direct nursing care to education, research and analytics, quality assurance/improvement, and consulting.