People with disabilities constitute one of the nation’s largest minority groups, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that there are more than 16,000 long term care facilities in the United States, with more than 1.6 million beds, 1.5 million residents, and an occupancy rate of at least 85 percent. American Health Care Association members currently have 8,476 Intermediate Care Facilities for Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities and Developmental Disabilities waiver beds.

All these numbers have faces—most importantly for this article, mouths that need proper oral care.

Having disabilities creates many disparities in receiving oral hygiene. Intellectual disabilities make it hard for the patient to understand the importance of oral hygiene, as well as retain information on how to properly clean the mouth. There are other inequalities that are common between physical and intellectual disabilities that interfere with patient care.

Oral Problems Linked To Disabilities

Having a disability often comes with its own unique oral findings, so it is important that people with disabilities see a dentist more frequently than the average person. Because a great portion of those with physical disabilities are elderly, it is no surprise that most of the oral findings of physical disabilities are age-related. These findings include root cavities, gum recession, denture lesions, fractured teeth, tooth loss, dry mouth, and trouble swallowing (dry mouth is the most common finding).

The elderly population has a high number of medications, which is linked to being the No. 1 cause of dry mouth.

With intellectual disabilities, oral findings include gum diseases, incorrect bite, trouble swallowing, delayed teeth eruption, and tooth loss. Down syndrome is a unique intellectual disability because it produces an increased risk of gum disease but, oddly, lowers the patient’s risk for cavities.

Better Toothbrush May Be Needed

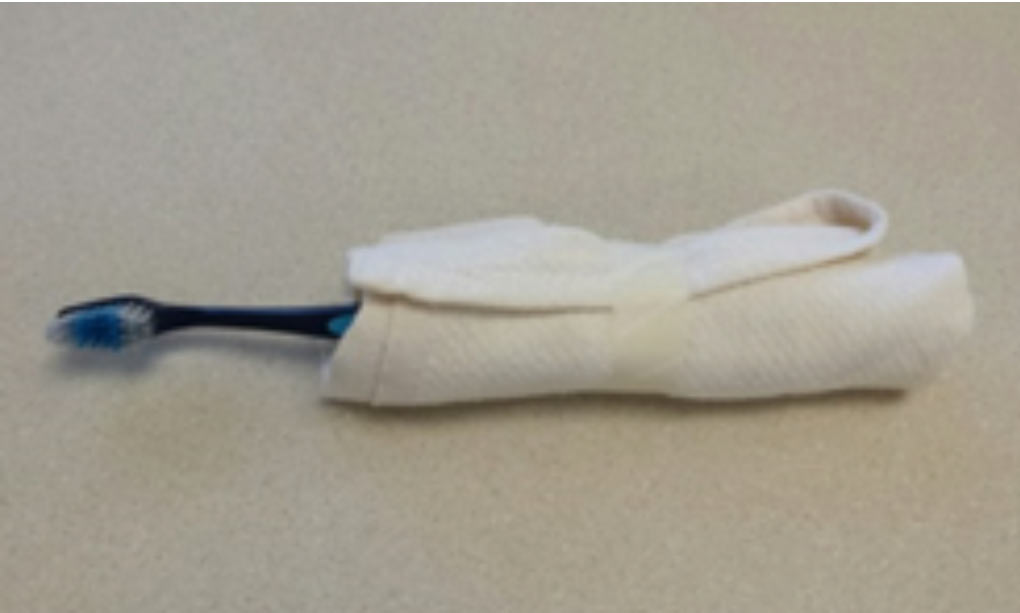

If the patient is unable to grasp the toothbrush, simple modifications can be made, such as adding a tennis ball or wrapping a washcloth around the handle for a wider grip.

A power toothbrush is designed with a larger handle for a better grip; there is no need for movement from the patient as the toothbrush provides the scrubbing motion to help those with limited range of motion or weak muscles.

Flossing can be challenging for those without physical disabilities, so for those with impairments it can be nearly impossible. Floss holders are a great way to assist those with limited dexterity.

Floss holders come in many different versions and should be adapted to the individual need of the patient. If the patient is unable to reach a sink or mirror, hand-held mirrors and basins can be implemented.

Don’t Forget The Dentures

Proper denture care is extremely important to avoid denture-related infections such as oral thrush, as well as overall oral comfort. More than likely, a caregiver assisting the elder population will come across a partial or full denture. It is important for oral tissues to breathe and be wiped of any debris before bed.

Soaking a denture in an over-the-counter antimicrobial mouth rinse every night should be implemented in the daily routine, as well as a thorough debridement of plaque before placing the denture back into the patient’s mouth.

Caregivers Walk The Line

Caregiving for those with an intellectual disability is a fine line between actively helping them with oral hygiene and knowing how much encouragement for self-oral hygiene to give. The caregiver should not do it for residents if they are capable: They should be given as much independence as they can handle.

Ultimately, the caregiver should assess their residents and know their limitations. Of course, they should step in and help when need be. This help will all depend on the severity of the intellectual disability. Those with a mild disability can do all of their own oral hygiene; all they need is encouragement and a set hygiene schedule. Explaining the importance of oral hygiene will motivate them, too.

Residents are more likely to cooperate and do a more productive job of brushing and flossing if they have incentive. Giving them a sticker or telling them they can join their friends or an activity circle after they brush their teeth are great ideas.

To help with anxiety, the caregiver needs to use the Tell-Show-Do method: The resident is told what is to happen, shown the process of treatment, and is administered the treatment. An intellectual disability makes it hard for the resident to understand what caregivers are doing most of the time. The Tell-Show-Do method shows them exactly what is going to happen and that they will not be harmed, and telling them after showing them confirms what they are seeing.

Mouth Rinse Essential

Due to the high risk for developing cavities among these individuals, a fluoride mouth rinse is crucial.

The use of fluoride rinses will need to be monitored closely. If the disability is too severe, a fluoride mouth rinse for a resident in an assisted living apartment, for example, may not be an option.

If the caregiver thinks the patient will swallow the rinse, it cannot be used. A great way to find out is to have the patient rinse with water and practice spitting it out before switching to a fluoride rinse.

In the case of a severe intellectual disability, the caregiver or loved one will be performing all oral care. The resident needs to be comfortable so he or she does not become combative.

A position that cradles the resident’s head in the elbow of the caregiver standing behind the person stabilizes the head and allows the caregiver to brush and floss the resident’s teeth.

Providing daily oral care for a person with a disability can be difficult. Understanding how to work patiently with the individual is the first step in becoming a skilled and proficient caregiver. Never hesitate to reach out to a dental professional for more information that may benefit the resident.

Emily Tepool, RDH, BS, can be reached at eetepool@eagles.usi.edu or (812) 781-9172. Jordyn Lewis, RDH, BS, can be reached at jordynlewis.10@gmail.com or (765) 719-1866. Emily Holt, RDH, BS, contributed to this article. She can be reached at erholt@usi.edu or (812) 461-5395.