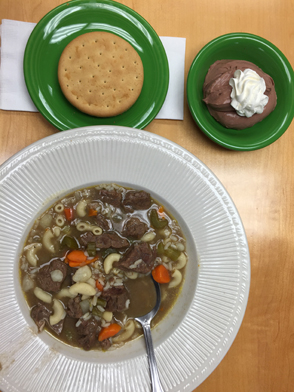

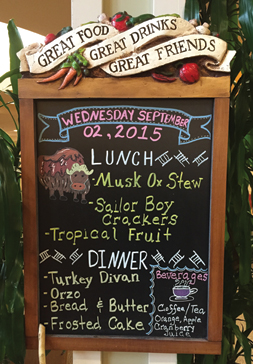

On Sept. 2, 2015, a long-time goal was finally realized when residents (Elders) of Utuqqanaat Inaat, an 18-bed nursing care center in Kotzebue, Alaska, were served their first traditional meal, musk-ox stew, out of the facility’s kitchen. This is the story of how one Alaskan facility collaborated with different government agencies to serve the foods its residents grew up on.

On Sept. 2, 2015, a long-time goal was finally realized when residents (Elders) of Utuqqanaat Inaat, an 18-bed nursing care center in Kotzebue, Alaska, were served their first traditional meal, musk-ox stew, out of the facility’s kitchen. This is the story of how one Alaskan facility collaborated with different government agencies to serve the foods its residents grew up on.

Beginnings

For years, the Maniilaq Association, a regional tribal health care nonprofit based in Kotzebue, had supported a unique nutrition program for the Elders in the community and at its senior center. Traditional foods such as moose and caribou were a staple provided by the program. It was modeled after a hunter/gatherer program where support in the form of stipends was provided for gas and bullets instead of food to communities.

Meat from wild game shot by local hunters was then distributed to the 11 villages in the Northwest Arctic Borough. In Kotzebue, there was a small processing building (Sigluaq, which translates to cold storage). The benefit to the program was that every $100 spent in supplies resulted in approximately $400 worth of meat in return.

In 2012, Maniilaq opened Utuqqanaat Inaat, a long term care (LTC) center, and when the Elders from the original senior center moved into Utuqqanaat Inaat, the old center was closed.

However, the regulations governing wild game were much more restrictive in a bona fide skilled nursing center. As a result, game was only served at a monthly potluck called Niqipaiq. In observing the residents after eating at Niqipiaq, it was obvious to managers how happy they were and how well they slept.

To try to serve traditional foods more often, the association worked on writing and helping to pass the U.S. Farm Bill of 2014. At the same time, work began to renovate a larger building to replace the old Sigluaq.

A Measured Approach

In order to have any success in serving traditional food, the first step was to pinpoint what foods were important to the residents. Their primary list included caribou; moose; berries; musk ox; sheefish, a type of white fish; salmon; ptarmigan; duck and geese; muktuk, that is, frozen whale skin and blubber; and seal oil.

There were two challenges: 1.) who would regulate the food the Elders were interested in; and 2.) determining the approved food source, according to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) guidance.

The U.S. Drug Administration (USDA) has a provision where certain exotic animals such as deer, buffalo, and elk could be slaughtered under voluntary inspections. Caribou, moose, and musk ox are not mentioned one way or the other. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) would get involved with exotic animals but only if interstate commerce was involved.

The U.S. Drug Administration (USDA) has a provision where certain exotic animals such as deer, buffalo, and elk could be slaughtered under voluntary inspections. Caribou, moose, and musk ox are not mentioned one way or the other. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) would get involved with exotic animals but only if interstate commerce was involved.

The Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) food code also allows traditional wild game meat, fish, plants, and other food to be donated to an institution or nonprofit program. Food has to be whole, gutted, quartered, or carved into roasts without further processing. Certain game meats, seal oil, and fermented foods are prohibited.

The Farm Bill-Agriculture Act of 2014 allowed for traditional foods to be donated to public facilities, including wild game meat, seafood, marine animals, plants, and berries. It is not as specific as the Alaska DEC food code regarding which wild game is accepted or not accepted.

The care center needed to find out from CMS which of the above listed agencies would be approving authorities. Under regulation 485.35(i) (1), aka F Tag 371, it says that its intent is to ensure that the facility:

Obtains food for resident consumption from sources approved or considered satisfactory by federal, state, or local authorities; and

Nursing care centers with gardens are compliant with the food procurement requirements as long as the facility has and follows policies and procedures for maintaining the gardens.

Making Calls, Building Collaboration

The first call made was to the USDA office that oversees Alaska, which is located in Denver. The UDSA director said that although the office had regulations for voluntary inspections of certain wild game such as deer, buffalo, and elk, it had no provisions for the slaughter of moose, caribou, or musk ox.

A follow-up conference call was then set up with USDA and the Alaska DEC, and together it was decided to turn jurisdiction for those animals over to the state of Alaska.

Another call to the Alaska DEC confirmed that the new Sigluaq would need a state permit. DEC was aware that an attached, but separately operated, hospital was hiring a sanitarian and liked that he would be overseeing the nursing care center on a regular basis.

The first collaboration happened in February 2015 over a conference call between the Alaska DEC, Maniilaq staff, and all pertinent agencies to discuss issues regarding traditional foods and skilled nursing centers.

Out of that meeting came clearer guidance to LTC centers about how they can serve traditional foods and the development of a seal oil task force.

Solving The Final Problem

Solving The Final Problem

Under the Alaska food code, wild game can be donated to an LTC center, but it doesn’t resolve who approves the food. Because Maniilaq built a Sigluaq where the meat was cut up, it required an Alaskan food permit. Once the permit was obtained, a meeting was set up with the Alaska DEC and the Department of Health and Social Services (DHSS). At the meeting, the DEC said that its permit would be the approving authority, which DHSS accepted, thus meeting CMS’ requirement.

Facility staff also spoke to DHSS about the garden regulation. As the facility had no traditional garden to speak of, could the tundra be considered its garden? The answer was a very positive yes.

Health Impact Of Commercial Foods

Aside from the cultural impact, there are health impacts as well. Traditional Alaska native foods are some of the healthiest foods in the world. Moose and caribou meat are very high in protein and low in saturated fat. Alaskan wild blueberries have more antioxidants than their cultivated counterparts.

When the switch was made to a commercial diet away from a traditional foods diet, obesity rates soared.

The Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium reports adult native Alaskan obesity rates of 35.4 percent, much higher than nonnative rates of 25.7 percent. By comparison, U.S. Caucasians are at 25.4 percent. Native Alaska adolescents are now slightly more likely to be obese than nonnative adolescents.

The Sigluaq Model

The Sigluaq Model

One of the advantages of using the Siqluaq is that it provides a reliable supply of the traditional wild game that had been a part of the residents’ subsistence lifestyle. From a precautionary point of view, the facility does not accept any wild game directly other than from the Sigluaq hunter support director. Because wild game has to be taken ethically, it adds another layer of protection to have one person inspecting and accepting donations.

There is another advantage for the facility to use the Sigluaq. Under Alaska food code, a facility can accept wild game either whole, quartered, or as a roast and fish gutted and gilled, no fillets. The reasoning from the state is that the hunter is not a meat processor. For the staff, it means an extra step in the meal preparation process. Through the Sigluaq, it can be processed further down into ground meat or fillets.

What’s Next

Looking back, much of what transpired was an exercise in getting different government agencies to work together on a common goal. The Sigluaq is but one approach that may or may not work for every nursing center.

The Maniilaq Association recognizes that this is a unique partnership with the government. For Maniilaq, the next step now is looking for a process for making seal oil that would win the approval of the Alaska DEC.

The Maniilaq Association recognizes that this is a unique partnership with the government. For Maniilaq, the next step now is looking for a process for making seal oil that would win the approval of the Alaska DEC.

By incorporating traditional foods into the menu, the residents are able to eat foods that they grew up on and maintain a connection with their community and subsistence lifestyle. The best part of serving native foods is seeing the residents smiling, eating everything on their plates, and sleeping well that night.

Valdeko Kreil, NHA, is administrator of Utuqqanaat Inaat, an 18-bed nursing care center in Kotzebue, Alaska. He can be reached at valdeko.kreil@maniilaq.org.