Most would agree that the statement: “The most secure health care system is one that nobody can access,” is true. However, as secure as it is, that system would be useless. In long term and post-acute care (LT/PAC), accessibility to relevant data is critical to quality outcomes.

Most would agree that the statement: “The most secure health care system is one that nobody can access,” is true. However, as secure as it is, that system would be useless. In long term and post-acute care (LT/PAC), accessibility to relevant data is critical to quality outcomes.

The converse would be a system that has no access control at all, where the user can launch the application and do anything they want to, without having to worry about remembering a password or user name—that system would be easy to use and even simpler for information technology (IT) staff to manage, but clearly that approach would not offer any data security whatsoever.

These are two extremes. However, the best systems, and the best security policies, will typically fall somewhere in the middle of the range of possible solutions for the security area in question.

A Common Predicament

Here is a real-world example: How does an LT/PAC organization handle a situation where a certified nurse assistant has forgotten his or her password, but needs to log into the electronic health record (EHR) to begin delivering care for the day?

Some customers may feel strongly that their users should only be able to have their password reset by staff from their IT department, so that the central office can fully validate that they are not giving access to an impersonator. (If not familiar with this technique, it is worth doing a Wikipedia search about “social engineering” for more information.)

Then there are customers who feel just as strongly that their users should have the ability to reset their own passwords through some form of self-service password recovery method. This is often an email-based system where the user enters their login name and clicks a link that triggers an email to the email address on file with a link to a page where the user can reset their password. It might also require them to provide the answer to a “secret question” that (presumably) only the user would know.

Embracing Uniqueness

It is important to note that neither of these solutions (centralized or self-service) is a wrong answer—every LT/PAC organization is different, with different operating methods and security environments, and user management can be centralized or decentralized, or even both at the same time.

The email-based approach is obviously only useful if all the staff have company email access, so its usefulness can be limited in LT/PAC. The secret question recovery method may be convenient, but be aware that the secret question method offers a larger (and additional) attack surface than just the username and password. If a hacker is targeting a specific user in the organization, it can be surprisingly easy to find or deduce the name of the high school the user graduated from, the make and model of their first car, or the name of their favorite pet.

“Secret-question-and-answer password reset systems are a way to allow a person into the EHR who doesn’t know a password.” Think about that one for a moment. When setting policies for user management, there is a decision to be made: Where is the organization’s sweet spot regarding the compromise between usability and security? Both are critical to success, of course.

Making Better Passwords

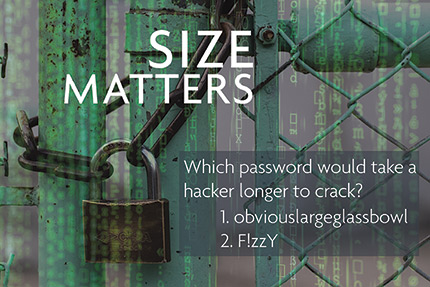

There’s also a duality between allowing simple, easy-to-remember passwords or requiring complex passwords, which seem more secure but can be harder to type, or harder to remember. Fortunately, there is less needing to compromise in this area than there used to be.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), until recently, recommended that passwords contain a mixture of upper-case, lower-case, numeric digits, and special characters. However, recent analysis has turned that on its head—NIST now advises that complex passwords are in many cases just as hackable as simple passwords of equal length.

However, the one factor that makes the biggest difference in terms of security is the LENGTH of the password. A password phrase that is a) not obvious and b) 20 or more characters long is virtually unhackable with current technology. So, if the EHR allows for setting a minimum password length, setting a longer length requirement will do more for the security than requiring special characters and so on.

One can advise users to think of a four-word phrase that they can remember and type easily, like, for example, ‘obviouslargeglassbowl,’ which according to one password evaluation algorithm, would take 410 billion years of computer time to decrypt.

Compare that to ‘F!zzY’, which could be broken in 43 milliseconds, according to the same evaluation. Fortunately, this security issue doesn’t necessarily require as much compromise as one might think.

Resetting Options

So, what is the best way to handle forgotten passwords? If the system offers an email-based password reset, that may a great solution, but only if the organization provides email accounts to most or all of the users, which may not be practical. Similarly, phone-based or text-message-based resets may or may not be feasible for the business case.

Another option is to require users to contact IT or other designated staff to reset their passwords, but for a large organization, this can require a lot of staff, and probably 24/7 coverage. It is good practice to do it this way, as long as the IT staff are trained to validate that the person on the phone is who they say they are. (See the earlier comment on “social engineering.”)

Another option is to require users to contact IT or other designated staff to reset their passwords, but for a large organization, this can require a lot of staff, and probably 24/7 coverage. It is good practice to do it this way, as long as the IT staff are trained to validate that the person on the phone is who they say they are. (See the earlier comment on “social engineering.”)

If it is not possible to provide 24/7 centralized password reset services to the users, then what? One might go with a decentralized approach where a few key staff at each location can handle password resets.

This also requires 24/7 coverage, but not necessarily dedicated support staff. The security trade-off here is this approach would require granting admin access to a larger number of people in the facility.

If the system offers a secret question-based password reset process, and the alternatives above are not workable, this may end up as the compromise that gives the best balance between security and usability when users forget their passwords. The caveat with that is the organization should advise users to choose a secret question that is not easily guessed or researched on social media.

Beefing Up Secret Questions

If the system has a predefined list of questions that they can choose to answer, encourage them to pick the less obvious questions, or if it allows the user to enter their own questions, encourage them to be smart about the questions they choose.

For example, the name of their favorite teacher might be harder to research than the name of their high school sports mascot.

The role of the technology partner is also important. A trusted technology provider should be constantly evaluating the LT/PAC business environment and emerging security threats, as well as new user authentication and authorization technologies as they become available.

Their strategy should be to offer highly configurable security options using the latest technology, so that their customers can configure the system with the right security options for their specific situations and business needs.

Striking a Balance That Works

Optimizing the security of any computer system involves a compromise with usability. But with careful evaluation of the various options available, providers will likely find a balance between the two that protects the data while keeping it easy for individuals to access the systems and care for the clients.

Joe Berkman is product manager at MatrixCare. He can be reached at Joe.Berkman@MatrixCare.com.