The challenge is to catch it early, reverse it when possible,

and balance interventions with personal preferences. This requires a

team where everyone is on the same page, communicates effectively, and

has the latest, best tools at their disposal.

The Many Ingredients of Weight Loss

Older adults are generally at risk for weight loss and malnutrition

because of the problems and deficits related to aging—some physical,

some mental or emotional, and others socioeconomic or cultural. All of

these issues can contribute to poor appetite and weight loss and a

cascade of conditions and illnesses.

The cause of weight loss may seem obvious—the person isn’t getting

enough calories and nutrients. However, it is much more complex. This

problem often results from a combination of factors. Among the many

problems that can contribute to weight loss and malnutrition are:

Dementia or other cognitive impairments that cause people to lose their appetite or forget to eat;

Malignancies or other illnesses, such as heart disease, thyroid disease, and infections;

- Depression;

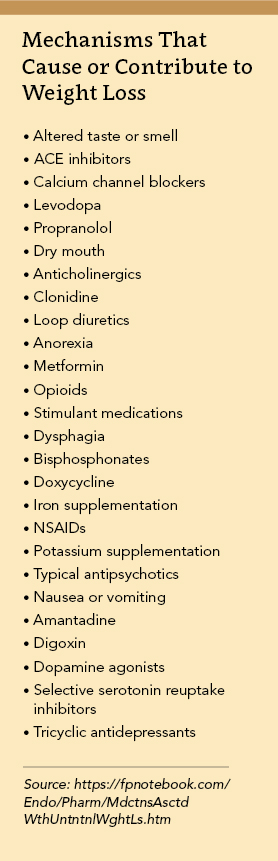

- Certain prescription medications (see table, below);

- Restricted diets;

- Lack of access to preferred foods;

- Limited income;

- Lack of transportation;

- Alcoholism or drug addiction; and

- Dental or oral health pain or problems.

Watch for Red Flags

It is important to note that unplanned weight loss in an elderly

patient should always be a red flag and should lead to some assessment.

“When I get a call from a nurse that a patient has triggered for weight

loss, I have a protocol that I use,” says David Smith, MD, CMD,

president of Geriatric Consultants in Brownwood, Texas. “Tier one

involves some historical questions and observations to uncover any

circumstances that would indicate common reasons for weight loss or

reasons that are uncommon but easy to identify—such as dental problems

or other oral issues, distorted body image, or dissatisfaction with the

food being served.”

Tier two of Smith’s protocol looks for issues that are a bit more

uncommon and are more expensive to evaluate, such as the presence of

swallowing problems or metabolic disease. If the cause is still

undetermined after tier one and two assessments, Smith goes to tier

three, which involves more invasive and costly assessments designed to

uncover issues such as a malignancy.

“People often jump to ‘cancer’ as a likely medical cause for weight

loss. In truth, there are many other more likely culprits—from heart

failure and thyroid issues to infections and depression,” says T. S.

Dharmarajan, MD, MACP, FRCP(E), AGSF, vice chair of the Department of

Medicine and clinical director of the Division of Geriatrics at

Montefiore Medical Center (Wakefield Campus) in Bronx, New York.

“If you encounter weight loss, you need to identify the root causes

as quickly as possible, and not make assumptions or leap to

conclusions,” says J. Kenneth Brubaker, MD, CMD, medical director of

Masonic Village in Elizabethtown, Pa. Start with the “low-hanging

fruit,” he suggests, such as drugs that may be causing or contributing

to weight loss, or the patient simply doesn’t like the food being

served.

Dharmarajan agrees, noting, “Sometimes if you just ask, you will

find out that it’s something fixable such as they can’t cut or chew the

steak, or they don’t like fish.”

Finding out why someone isn’t eating requires a bit of detective

work, Dharmarajan says. The person’s plate is one important clue. “Look

at the patient’s tray after he or she eats. You can see what and how

much they’re eating,” he says.

While drugs that help depression can lead to improved appetite,

Smith says that several nonpsychiatric drugs—such as clonidine,

digitalis, levodopa, prazocin, reserpine, amiodarone, and

steroids—actually can cause depression and negatively impact appetite

and eating.

Even if there is a medical problem, it can be fixed fairly easily.

For instance, Dharmarajan says, “I had a new resident who told me that

she had no appetite for anything. I asked her simply, ‘Do you miss your

grandchildren?’ She started crying. I put her on antidepressants, and

within a few weeks, she was eating again. Her daughter thanked me for

giving her ‘mom back’ to her.”

When Patients Live Alone, Nutrition May Suffer

Particularly when older people live independently—either in the

community or senior housing where they have their own apartment—weight

loss and/or malnutrition often stem from issues that are easily

addressed.

“When they live alone, they often eat alone; and they may eat less.

Or they don’t want to cook for one and will skip meals or eat fewer

balanced meals,” says Marcie Rittenhouse, RDN, CSG, a consultant

dietitian at central Pennsylvania-based LIFE/PACE program. “Some don’t

have family checking in on them regularly, so no one notices at first

when their eating habits change or they start to lose weight.” Even

those elders who live with family can be at risk.

“We have some older people who live with an adult child or other

family member who also eats poorly,” she says. In these cases, an

occupational therapist or social worker can make home visits and

identify issues, such as Mrs. Smith doesn’t know how to use her

microwave, or Mr. Jones needs a way to get to the grocery store.

Sometimes, the solution is as simple as helping to schedule rides to the

store with a neighbor or arranging for the person to participate in a

Meals-on-Wheels program or eat lunch at a local senior center.

Encouraging Elders to Eat

For residents of an assisted living community, they may just need

some encouragement and incentive to go to the dining hall for meals. For

instance, staff can introduce them to other residents who they can eat

and socialize with.

In some instances, a more complex and urgent intervention is

necessary. “Sometimes elders are in dysfunctional family situations that

are affecting their ability to eat well. For instance, they have an

adult child who has an alcohol or drug problem,” says Rittenhouse.

It’s important to realize that people have varying views about and

relationships with food. For instance, Rittenhouse had one patient who

lived with her daughter, who firmly believed that mom should sit at the

table and eat a full hot meal. She was upset because her mother was

resistant. “I had to remind the daughter that her mom is in her 80s and

doesn’t need as many calories or as much food as a younger person,”

Rittenhouse says.

She says another family wanted to use food as a reward or incentive

for certain behaviors. “Food should never be used as a punishment or

reward, and we shouldn’t pressure or force people to eat,” Rittenhouse

says. “We should let them eat when they are hungry, and help ensure that

they get food they enjoy.”

Communicating Choices

Sometimes, it may be difficult for families and caregivers not to

impose their own feelings about food onto an elder. For instance,

Rittenhouse worked with one woman who was emaciated but resisted eating

more because she “likes to stay trim.”

If someone is very thin, Dharmarajan says to do a Body Mass Index

(BMI) test and assess them for any problems. “If there are no red flags

such as an excessively lower BMI, physical weakness, falls, depression,

isolation, or lethargy, we shouldn’t push him or her to eat more,” he

says.

Smith adds, “You must determine whether this is just cultural and

‘normal’ thinking or a psychological disorder, such as anorexia

tardive.” He says that a psychiatric exam might be in order.

To help determine if there is a body image issue that may need to

be addressed, ask patients to clip pictures from a magazine of people

they identify as “too thin,” “thin,” and “obese.” This type of exercise

can be very revealing, he says.

Such personal beliefs, as well as cultural issues and preferences regarding food, should be identified on admission.

“My mother is a lacto-ovo vegetarian, and we made sure the nursing

staff at her facility knew this from the start,” Dharmarajan says. “I

told them that she particularly loves yogurt, which she ate all her

life. But I also told them that she can have anything she wants to eat,

although she has diabetes.” At her stage of advanced dementia, her

quality of life was more important, and avoidance of restrictive diets

was at the top.

Facility staff should meet with families within a few days of

admission to have a care planning conversation that includes a

discussion of food and dietary preferences, including a review of

medications, Dharmarajan says. He also recommends a nutritional

evaluation of the patient on admission to determine if they are

malnourished or at risk for malnutrition. He also recommends a

nutritional evaluation of patients on admission to determine their

nutritional status.

Patients often come from the hospital deconditioned and

malnourished, particularly after a long illness, he says. “We need to

assess them early and determine what needs to be done to help them

recover their strength, regain lost weight, and be as nutritionally

sound as possible given their condition,” he says.

Dietary Restrictions: Less Is More

Clinicians do not generally recommend restricted diets for older

nursing facility residents, particularly those with a life expectancy of

five years or less. “Generally, we allow these patients to eat what

they want,” says Brubaker.

There have been many studies about the value of certain kinds of

diet for cardiovascular and brain health as people age. However, Smith

says, “Nutritional research related to diet and outcomes is fraught with

difficulty, and the methodology for many population-based nutritional

studies is flawed.” Nonetheless, he notes that the Mediterranean diet

has been shown to have some value.

“Here in Texas, the Paleo diet is catching on. The philosophy is to

emulate the diet of our cave-dwelling forefathers with a focus on meat

and vegetables and a de-emphasis on simple carbohydrates and sugars,” he

says.

While a healthy diet for all is ideal, maintaining weight and

strength is a key goal for the elderly, and this often requires

flexibility. “In the not-too-distant past, we were recommending

therapeutic diets for the elderly; then expert opinion determined that

these diets don’t really benefit this patient population because of

their shorter life expectancy,” Smith says. However, he stresses that

restrictive diets are appropriate for younger nursing facility patients.

“While we can’t make them eat healthy, of course, we should always

educate younger patients about why they should or shouldn’t eat

different foods,” Smith says, admitting that this can be challenging

when patients have limited mental capacity or an inability or

unwillingness to hear and retain information.

Dharmarajan stresses the importance of discussing liberalized diets

with family members up front. “If a man had been a diabetic for years

and was on a strict diet, you don’t want his family to see a cookie on

his tray and get upset. You want to help them understand why you are

liberalizing their father’s diet,” he says.

Brubaker agrees that these family discussions are essential. “Some

families are very committed to things such as tight diabetic management.

However, when we talk to them about the benefits of a liberalized diet,

most will understand,” he says.

Are Supplements Super?

“I would rather patients eat food than spend their money on things

like vitamin waters, energy drinks, and vitamin or herbal supplements,”

says Rittenhouse. Another problem with these is that they can be costly.

“We had a woman who was buying $2 bottles of mineral water that she

couldn’t afford, and whatever benefit she might be getting from it

wasn’t worth the cost. We have to consider what is affordable, as well

as what will produce the best outcomes.”

Appetite stimulant medications might seem like a quick fix, but

Smith cautions against them. None is approved by the Food and Drug

Administration for use by the elderly, he says. At the same time, most

appetite stimulants are expensive and have more risks than benefits for

this patient population. It is better to evaluate patients and find the

root cause of weight loss, he says.

Skilled nursing facility patients generally have a need for or can

benefit from nutritional supplementation, such as vitamin D, Smith says.

However, he says, “These patients don’t need more pills, and nurses

don’t need more med passes to make.” One solution might be food

additives, Smith suggests.

“Fortify the ‘real food’ so that it better meets the resident’s

needs. This could be done across the board so all residents get the

benefit. Of course, additives can be individualized to resident needs

when giving something to everyone isn’t appropriate or necessary,” he

says.

How Surveyors See Weight Loss

The prevalence of weight loss is a quality indicator for skilled

nursing centers, and regulations state that facilities must ensure that

residents maintain acceptable parameters of nutritional status, such as

body weight and

protein levels, unless a resident’s clinical condition

demonstrates that it isn’t possible. According to the Investigative

Protocol for Unintended Weight Loss in nursing centers, a more than 5

percent unplanned drop in weight after a month, greater than 7.5 percent

after three months, and 10 percent after six months are considered

“significant” losses.

To help ensure that surveyors understand the reason for unplanned

weight loss, it is important to document regular weights, interventions

taken, and discussions with the patient and/or family members regarding

nutrition and weight.

It is important to document efforts to balance patient choice with

sound clinical care. This isn’t always easy, Smith admits. “I have

encountered surveyors who say that a resident has the right to eat

whatever he or she wants, even if the person’s legal guardian and I both

agree that the resident shouldn’t be able to spend money on candy and

sodas. We have to protect the resident’s rights. But it’s also our

responsibility to take charge of decision-making areas where they lack

capacity.”

“Staff often worry that weight loss will result in survey

citations,” Dharmarajan says. “But surveyors just want to be sure that

patients aren’t losing weight because they aren’t getting enough to eat

or the food is of poor quality.”

It is key to document how weight loss is assessed and addressed;

what care goals related to weight loss are established; and the progress

made on the approach, including conversations about the issue with the

patient and/or family members, he says. This documentation will show

surveyors that staff have identified the problem, are managing it

appropriately, and are respecting the patient’s wishes and

autonomy.

The Trouble with Tube Feeding

Dysphagia,

especially as a patient nears the end of life, often leads to

conversations about tube feeding. “Family members sometimes believe that

a PEG [Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy] tube will help their loved

one and make him or her feel better,” Dharmarajan says. However, “The

reverse is true. This intervention doesn’t increase life expectancy or

improve quality of life.”

Nonetheless,

family members or decision makers often are influenced by factors such

as misperceptions about feeding and hunger, an inadequate understanding

of the natural course and progression of dementia, lack of understanding

about evidence regarding the risks and benefits of tube feeling, and

cultural or religious beliefs. This is where a good practitioner-family

relationship is so important, he says.

“No tube is placed without informed, educated consent, and this

requires a serious conversation with the patient and/or his family or

decision maker,” Dharmarajan says. The decision about a PEG needs to be

based on understanding and weighing the risks and benefits, not on

presumptions. Undue expectations should not be offered.

In instances where the patient lacks decision-making capacity, has

no living will, advance directive, or designated decision maker,

“Clinicians must assume that a patient wants nutrition therapy until

proven otherwise or until evidence is found to the contrary,”

Dharmarajan says. However, there is much controversy surrounding the

ethics of placing PEGs in patients for whom there is reduced or limited

clinical benefit. This intervention is associated with complications

that may be related to the tube itself, aspiration pneumonia, and

pressure ulcers.

In advanced dementia, PEGs are typically placed to prevent

aspiration and pressure ulcers, improve function, and prolong life

expectancy. However, the risks in reality outweigh the benefits,

Dharmarajan says. For instance, patients can’t move with the tube

inserted, so they become bedbound and susceptible to pressure ulcers,

deconditioning, muscle weakness, and other issues. Also, he notes,

“Converting from hand feeding to a PEG deprives the patient of touch,

taste, nurturing, and social interaction.”

In fact, family members or caregivers often are the ones who gain a

real benefit from a PEG. “The family’s or caregiver’s quality of life

usually improves, as their frustrations may be tempered and they

believe—falsely—that they are preventing their loved one from suffering

due to hunger or thirst, he says.

An honest, open conversation with the family can help clear up

misconceptions. However, this isn’t always the case. “Sometimes, a

family member is insistent, even after being presented with all of the

information and facts,” Brubaker says. “Often this is because they are

dealing with their own feelings about death and dying.”

When this happens, he says, it may be helpful to refocus the

discussion on what their loved one would want. “We need to be aware of

this and try to determine why someone insists on a PEG, even when the

risks outweigh the benefits.”

Sometimes Weight Loss Is Welcome

Obesity is epidemic in the United States, and it is problematic in

nursing centers as well. “We are seeing more obese patients, and they

often have related problems such as diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and

vascular problems,” says Brubaker.

“We can’t expect people to change lifelong habits late in life, but

we can try to reduce caloric intake and have discussions about diet and

nutrition.”

“You won’t perform miracles with obese patients, but we can always

attempt to help them lose some weight and be healthier,” says

Dharmarajan. “This includes trying to get them to be more active, if

possible.” He says it is important to be positive and encouraging and

not make patients feel bad. “Set realistic targets for weight loss, and

always praise the patients for positive behavior.” Help them understand

how weight loss is related to quality of life.

Particularly for younger patients, bariatric surgery might be an

option, Dharmarajan says, but the first approach is always to address

lifestyle: diet and physical activity. Always individualize, taking into

context the individual’s overall illness and life expectancy.

Don’t Wait on Weight

Having the ability to monitor weight and quickly address weight

loss is essential to keep patients as happy and functional as possible

and, importantly, to keep them out of the hospital. “In the hospital,

deconditioning happens remarkably quickly, and many patients come to us

with malnutrition,” says Smith.

Being proactive and staying on top of weights is essential. At the

same time, facilities can be creative about ways to encourage resident

nutrition and healthy weights. For instance, Kings Harbor in New York,

which caters to Indian seniors, has chefs and dietary teams who make

authentic Indian meals. The Lott Residence, also in New York, has its

dining hall on a top floor so that residents can enjoy a breathtaking

view of the city while they eat.

Other facilities have private dining areas where residents can cook

and eat with family members, and many communities offer special meals

and celebrations featuring ethnic and regional foods popular among their

residents.

“Put yourself in your patients’ shoes,” Dharmarajan says. “If you

serve foods I don’t like, I’m not going to eat them. Food is one of

life’s great pleasures, and we need to enable our residents to preserve

this joy for as long as possible.”

Joanne Kaldy is a freelance writer and communications consultant based in Harrisburg, Pa.